Only the dead have seen the end to war.”

Thursday, September 28, 2017

The Wars by Timothy Findley. A Margie Taylor Review

I have never met anyone who could expose the heart of a book like Margie Taylor. Here is her powerful review of a Canadian classic.

Only the dead have seen the end to war.”

Only the dead have seen the end to war.”

George Santayana wrote this

in 1922. He was responding to the idea, popular at the time, that the First

World War was the war to end all wars. It was the Great War for Civilization. The

war that would be over by Christmas.

It wasn’t any of those

things, of course. In the end it dragged on for 4 years, 3 months, 11 days. It

took the lives of 9 million soldiers, 7 million civilians, 8 million horses and

countless mules and donkeys. And 21 years later we did it all over again.

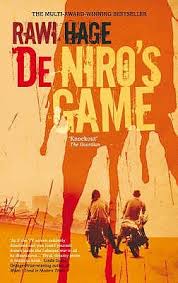

There’ve been many books

dealing with this, the first great European war. A Farewell to Arms

comes to mind…All Quiet on the Western Front…Goodbye to All That…the

four novels by Ford Madox Ford collectively known as Parade’s End. More

recently, we have Birdsong … War Horse … Pat

Barker’s Regeneration Trilogy.

And The Wars by

Timothy Findley. When it was published in 1977 it was immediately hailed as one

of the best stories about that ghastly war. It won the Governor General’s Award

for English-language fiction and quickly became a literary classic. It’s been

called the finest historical novel ever written by a Canadian and has been

required reading for high school students for years. This is in spite of the

efforts of an Ontario mother to get it removed from the curriculum.

Fortunately, she was unsuccessful.

The hero of the story is

Robert Ross, a sensitive 19-year-old Canadian officer who joins up to

fight out of guilt. His beloved older sister has died and Robert, who

believes he should have been there to save her, blames himself for her death.

Like so many of his countrymen, he has an idealized vision of war. It will be

the fire that will purify his soul … the crucible that will forge his manhood.

What he is not expecting is that it will destroy him – that his experiences on

the Western Front will drive him to the verge of madness and beyond.

The “wars” within the novel

are internal as well as external: guilt, shame, sexual tension, the struggle to

adapt to a way of life that increasingly makes no sense. And the conflict

between the way things should be, in a rational world, and the way they happen

in war. In the maelstrom of war there is no right or wrong. There is only the

imperative to follow orders. One’s moral code means nothing.

Findley has chosen to tell

Ross’s story from the viewpoint of a historian or biographer who has access to

photographs, letters, and documents from the soldier’s past. He – or she – is

also able to interview some of the people who knew him. And so we have a

narrative told from various perspectives – the anonymous researcher, the nurse

who cared for Ross in his final days, the woman who fell in love with him when

she was twelve.

But it is this fragmented

approach that prevents us, I think, from seeing Ross himself. Or rather, seeing

into him, as opposed to observing his reactions to the chaos of his

surroundings. Before leaving England for France, Ross is taken to a

brothel where he ejaculates prematurely. The woman is kind … she assures him

that “there’s lots of fellows do what you done. Specially the first time.” We

are told Robert is ashamed, staring at the floor, but the narrative voice is

distant. It simply doesn’t feel personal.

Later, in a bath house in

northern France, he’s locked in a dark, airless room and raped by his fellow

officers. He thinks there are three of them but has no idea who they are. It’s

a horrific scene but the reader is detached, watching from the sidelines.

It’s in the descriptions –

and there are many – of the war itself that we come to experience real, raw,

even violent sensations. Findley thrusts us into the trenches along with the

soldiers – drowns us in mud and blood and dead horses, cracks our eardrums with

the blasts of exploding shells, blinds us with clouds of chlorine gas. In

unforgettable prose, he describes the effects of the flammenwerfer,

or flamethrowers, introduced by the Germans at the Battle of Verdun – a battle

in which the French army suffered 380,000 casualties:

“Fire storms raged along the

front. Men were exploded where they stood – blown apart by the combustion.

Winds with the velocity of cyclones tore the guns from their emplacements and

flung them about like toys. Horses fell with their bones on fire. Men went

blind in the heat. Blood ran out of noses, ears, and mouths.”

The greatest terror, for

some, is that the officers in charge, the men who are sending thousands of

soldiers to slaughter, may not actually know what they’re doing: “What if they

were mad – or stupid? What if their fear was greater than yours? Or what if

they were brave and crazy – wanting and demanding bravery from you?”

Their fears are well

grounded. Commanding officers are far removed from the front lines. They

make “strategic” decisions guaranteed to put their men in harm’s way … mistakes

that cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

On the 16 of June, 1916, Ross

commits a final desperate act. Under siege from the Germans, with shells

bursting all around him, he breaks rank and releases a barn full of horses and

mules who are in danger of being burned alive. His captain, calling him a

traitor, closes the gates and tries to kill him. Ross, in turn, shoots the

captain between the eyes. For this act of treason – a violent gesture declaring

“his commitment to life in the midst of death” – Ross is eventually captured

and tried in absentia. By this time he’s burned beyond recovery; his

nose is disfigured and bent, his face is a mass of scar tissue. He will never

walk or see or be capable of judgment again. He dies in 1922, at the age of 25.

I cannot think of a better

introduction to the horror, brutality, and near insanity of trench warfare than

this particular story. If I never read another tale of that terrible war, I

will consider myself educated.

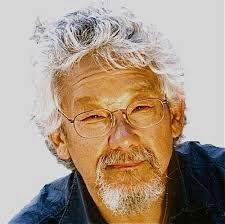

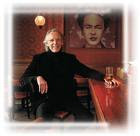

Timothy Findley

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment