Wednesday, November 29, 2017

Wuthering Heights Reviewed by Margie Taylor

It is a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.”

So wrote an American critic in 1848 upon publication of Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë’s first and only novel. He was not alone. Shock, disgust and bewilderment were the most common reactions, with one reviewer even suggesting the book should be burnt. Published under the pseudonym Ellis Bell, this dark, imaginative tale of the power of love to transcend the grave challenged almost every Victorian ideal of morality, justice, and heroic behaviour.

Had readers known the author was a woman, the reaction would have been stronger. But by the time the truth was revealed, thanks to a second edition published in 1850, Emily Brontë was dead of tuberculosis at the age of 30. Two sisters and a brother had died before her, and another was quick to follow. Her older sister Charlotte, the author of Jane Eyre, was left to mourn her sisters, and retrieve their public reputations.

While Charlotte believed her sister was a genius, she felt compelled to explain the book and its characters to outsiders – those readers who knew nothing of the author or the people who inhabited her part of the world. In a preface to the second edition she writes, “To all such people…’Wuthering Heights’ must appear a rude and strange production.”

“My sister Emily was not a person of demonstrative character … [her] disposition was not naturally gregarious; circumstances favoured and fostered her tendency to seclusion; except to go to church or take a walk on the hills, she rarely crossed the threshold of home. Though her feeling for the people round was benevolent, intercourse with them she never sought; nor, with very few exceptions, ever experienced.”

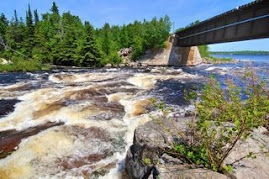

It was this very isolation that nurtured Emily’s romantic nature and gave birth to the wild, romantic and otherworldly tale set in the place she knew well – the bleak and beautiful Yorkshire moors.

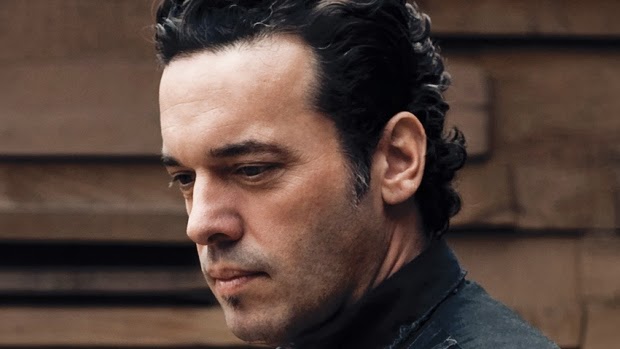

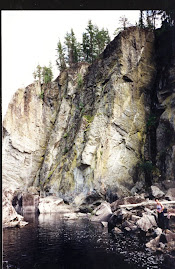

The story begins in November 1801 when Mr. Lockwood, a rather vain and pretentious gentleman, rents Thrushcross Grange, a large house situated on the edge of the remote moors of West Yorkshire. On arrival, he decides to pay a visit to his landlord, who lives four miles away in the ancient manor house known as Wuthering Heights. The visit is not a success; the landlord, known only as Heathcliff, is dark, surly and unfriendly, with a temper that verges on violence. He does not welcome visitors and only reluctantly calls his dogs off when they attack. In spite of this cool reception, Lockwood pays a second visit a few days later. This time he meets the other occupants of the house: Hareton Earnshaw, a good-looking but coarse, quick-tempered and illiterate young man; Catherine Linton, a beautiful but deeply unhappy young widow, and Joseph, an old servant who speaks with an almost indecipherable Yorkshire accent.

A blizzard prevents Lockwood from making the trek back to the Grange – reluctantly, Heathcliff agrees to let him stay for the night, and he’s locked into a room that is never normally used. During the night he discovers a diary written years ago by Catherine Earnshaw, a young girl who seems to have a special relationship with the young Heathcliff. He falls into a troubled sleep and wakes to the sound of a tree branch brushing against the window. Still half asleep, he forces his hand through the glass, determined to remove the branch, and finds himself grasped by the cold, icy hand of a young woman, begging to be let in. In an effort to free himself, he rubs the ghostly hand against the broken glass till the blood runs onto the sheets. His terrified shouts finally alert his landlord, who enters the room, cursing him for the disturbance. But when Lockwood tells him the room is haunted, Heathcliff rushes to the window, calling out to Catherine, begging her to return. Lockwood decides that, storm or no storm, he’s had enough of Wuthering Heights for one night. Heathcliff escorts him back to the Grange, where the servants are delighted to see that Lockwood is alive, having assumed he was lost in the storm.

Back in the safety of the Grange, Lockwood learns that his housekeeper, Nelly Dean, knows Wuthering Heights very well. She lived there as a child and grew up with the children of the house. He prevails on her to tell him the history of the manor and its strange inhabitants; she agrees to do so, and Lockwood writes the story from her recollections.

As she tells it, Heathcliff – whose origins are unknown – is found abandoned on the streets of Liverpool and brought back to the Heights by the kindly Mr. Earnshaw. His own children, Hindley and Catherine, don’t take to the “gypsy” child but gradually Heathcliff and Cathy form an attachment – an attachment that grows to the point where they become inseparable. They spend their days playing out on the moors; the greatest punishment for either of them is to keep them apart. Mr. Earnshaw, too, loves the boy – more so than his own son, which fosters even greater resentment on Hindley’s part and strengthens the bond between Catherine and Heathcliff.

The break between them comes when Catherine chooses respectability over passion. She marries Edgar Linton, whose father owns Thrushcross Grange and who, although weak and tiresome, loves her and will make a “good” husband. The marriage doesn’t last long: Catherine dies giving birth to a daughter – the Catherine Linton mentioned earlier – and Heathcliff is plunged into a dark well of despair verging on madness. Near the end of the book, he confesses to Lockwood that he is haunted by his lost love every minute of the day:

“[H]er features are shaped on the flags! In every cloud, in every tree – filling the air at night, and caught by glimpses in every object, by day I am surrounded with her image!”

In Catherine, Brontë created a heroine who was the embodiment of nature itself – tempestuous and pleasing by turns, afraid of nothing, living by her own rules. As Nelly describes her, “A wild, wick slip she was – but she had the bonniest eye, and sweetest smile, and lightest foot in the parish”. You could not help but love her.

How different is this from the quiet, painfully shy author of the book – who lived within the bounds of a strictly religious household, the dutiful daughter of a parish curate? In her innermost heart I believe she nurtured a free-spirited creature – a child of nature unfettered by convention. Catherine was that creature.

It’s telling, I think, that Brontë, the daughter of a curate, saves her most contemptuous descriptions for the character of Joseph, the old servant who sermonizes and preachifies at every turn. At one point she has Nelly Dean describe him thus: “He was, and is yet, most likely, the wearisomest, self-righteous pharisee that ever ransacked a Bible to rake the promises to himself, and fling the curses on his neighbours.” As curates and other men of the church were their only suitable male companions, Brontë and her sisters likely knew them well. We can hope they were not all as “wearisome” as Joseph!

But it’s the character of Heathcliff that fueled the moral and critical outrage over the book, and continued to do so for half a century. While he’s as handsome and tormented as befits a romantic hero in the Gothic tradition, he’s unremittingly cruel, sadistic and, quite frankly, evil. His behaviour is particularly hateful towards his son, Hareton, whom he’s raising as an illiterate farm hand in revenge for past wrongs. Right to the end Heathcliff is dark and unrepentant; there is something almost ghoulish – vampirish – in the way he looks forward to the time when he will be dead and buried, reunited with his love, Catherine. Strong stuff, this, even for modern readers.

In her preface, Charlotte assures us that if Emily had lived longer “her mind would of itself have grown like a strong tree, loftier, straighter, wider-spreading” … in other words, she would have matured to become a better writer. Still, she concedes the “very real powers” of the novel:

“Whether it is right or advisable to create beings like Heathcliff, I do not know; I scarcely think it is. But this I know; the writer who possesses the creative gift owns something of which he is not always master – something that at times strangely wills and works for itself.”

It’s regrettable that Emily Brontë didn’t live to write other novels but I don’t believe she could have written anything better. Wuthering Heights contains within it that unnatural beauty of expression few writers ever achieve. I hold it dear to my heart.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment